The profession offish cannery worker

From its origins in the early 19th century, the production of canned fish has been labour intensive. In the past and today, the majority of the staff working in coastal canneries are women.

Remuneration

This source of income was, in many ways, very precarious. Throughout the nineteenth century, women's work in fish canneries was the most underpaid of all industrial occupations[1] on a national scale. Unlike many industrial women's occupations that are paid by the hour, such as weaving, spinning and sewing, the work of women fish factory workers was for a long time paid by the batch of a thousand canned sardines. This form of remuneration was particularly random and arbitrary. The pay was never paid on a regular basis and the counting was generally done to the disadvantage of the employees. Wage increases and the securing of wages were particularly slow throughout the 19th and first half of the 20th century. It was achieved as a result of several strikes led by workers in various canneries along the Atlantic coast, particularly in Brittany.

Revolts and strikes

The first revolt by female employees in the fish processing sector was recorded by the historian Jean-Christophe Fichou in May 1889 on the island of Yeu. Although the historian's observations lead him to assert that the vast majority of female staff in the coastal canneries were resigned to the working conditions in this sector of activity, a few strikes in the south of Finistère were nevertheless to leave their mark on people's minds and bring about changes in the profession's regulations. The pioneering town that played a decisive role in this evolution was Douarnenez. The workers of this Breton port town were particularly supportive and persistent in their approach. Two of their strikes lasting several months have gone down in history, in 1904-1905 and 1924-1925. These strikes were covered exhaustively in the press of the time and led to the publication of numerous books as well as several online articles on the subject, such as those written by the local history enthusiast Gaston Balliot on his blog[1]. Another revolt that also received significant media coverage and left many archival traces was that of the women workers of the Bigouden region, and more particularly the employees of the Lesconil and Guilvinec canneries between 1926 and 1927[2].

These various strikes led to a relative improvement in working conditions as well as a change in the method and rate of pay for female workers. The latter were paid by the hour, at an hourly rate set at 1.35 in Bigouden country, at the end of the 1920s. However, these rights were not acquired in a homogeneous way throughout the fish canneries. The unionisation of female employees was only a real success in Douarnenez, and to a lesser extent in Concarneau and Lesconil. Female cannery workers in the rest of the coastline were less organised. Hourly pay was therefore not achieved in some factories before the Second World War. Hourly rates were left to the goodwill of each factory owner, as shown by the list of hourly wages for female workers in French canneries between 1847 and 1940 drawn up by Jean-Christophe Fichou in the appendix to his article on the workers' unions of the fish canning industry in Brittany[3].

Working conditions

In addition to being underpaid and precarious, work in fish factories was particularly physically demanding until after the Second World War. The days were long, more than 12 hours on some days, before the 1919 regulation on the 8-hour day in continuous-fire factories, a regulation that was hardly applied by factory owners in the first decades that followed (1920-1930). The hours went on, sometimes until after midnight. The most fragile workers gave up after a few hours of trial. It was physical and hard work that required a strong body and mind, as well as good health.

In addition to working hours, which are particularly long in the factory, there is an aggressive environment for all the senses. Hearing is put to the test by the noise of the mechanical machines, the crackling of the frying pans, the slamming of the transmission belts of the crimping machines, the pressure that escapes from the autoclaves, the empty metal cans that are poured onto the tables and the full cans that are knocked against each other during the quality control. The sense of smell is subject to the powerful odours of raw flesh from the fish cut up and dried in the drying tunnel, of tripe thrown into the bachots, of salt from the brine tanks and of fried oil in the frying tanks. The touch is not spared, with the risk of cuts during the heading of the fish or the crimping of the cans as well as the risk of burns during the sardine frying stage.

The entire body is put to the test by the prolonged static postures, whether sitting on a rigid bench without a backrest, or standing over the various workstations, or by the mobile postures aimed at carrying heavy loads such as brine containers, stronk containers, grills filled with sardines, but above all the wooden crates full of filled cans that have to be loaded onto the vans for the dispatch of the goods. These repetitive gestures wear you out on a daily basis.

The workplace was also not adapted to seasonal temperature fluctuations, nor was the clothing of the time. In summer, the factory was a furnace under the roof with the heat emitted by the steam and coal-powered machines and the high temperature of the frying pans. In winter, the workshop is a wet well. The floor is regularly wet with rinsing water. The workers' hands and feet are constantly in the water. The skin is not always resistant to this and frostbite makes the work painful. To escape the wet and cold, some workers put their feet up on small stools. The clothes are not waterproof either. They were the clothes of everyday life: clogs, socks, skirts, aprons with bibs, blouses, small short shawls or thick woollen cape.

The song

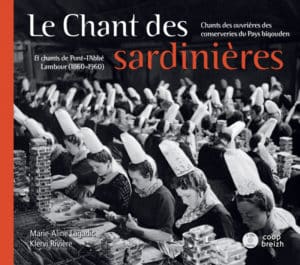

Contrary to the watered-down portrait painted by the press at the time, singing in the factory was not a sign of any kind of joy in the work. The workers sang to keep up, to fight against sleep during the endless hours of work that continued into the evening, to keep up with the pace imposed by the employers in a logic of profitability and productivism. These songs are now part of the Breton coastal heritage and have been collected and transcribed, as in the book The song of the sardine boats[1] co-authored by the two oral memory collectors, Marie-Aline Lagadic and Klervi Rivière.

Hierarchy

Not everyone in the factory is on the same footing. In addition to the classic disparities in wages between men and women, there are also differences between female workers according to age, seniority and the level of difficulty of the job.

Women workers in the middle range are called "ordinary workers". They earn a few cents more than the apprentices. They work at topping, cooking, packing, oiling, quality control.

The workers at the top of the hierarchy are slightly older. They are 'posted' to a specific job, such as crimping, and are paid more because of the skill and danger of the job. They are just below the forewoman.

The forewoman is the best paid of the workers. She is the eyes and ears of the bosses in the factory and reports to them daily. She constantly controls the workers: hours, quality of work, output. She generally came from a neighbouring area, not the local parish, because she was generally feared and/or hated by the other employees. At the Le Gall factory, the forewoman came from Douarnenez. She is housed in the house adjacent to the factory where the welders' boxes initially lived under the previous manager. From her accommodation in the factory house, a small window allows her to keep an eye on the factory at all times.

Perception of the profession

In addition to the hardship of the job, the perception of the inhabitants of the coastal areas is very negative. In the ports, everyone knows how hard the life of a sardine worker is. The women who could afford it avoided factory work by all means. During the population census campaigns, those who have benefited from training in Irish lacemaking or have learnt on the job with their relatives, prefer to highlight this know-how by designating themselves as lacemakers or embroiderers rather than sardine-makers, even if they only carry out this craft as a second activity, in parallel with their job as workers, in order to supplement their income.

Several terms commonly used by the Breton population bear witness to this pejorative perception of the trade. In addition to the term "sardinières" rather than "workers", the population also referred to these workers as "frying girls" because of the strong smell of oil that they carried when they left work and from which they had difficulty escaping, in spite of careful grooming. The inhabitants of the ports, particularly the wealthier classes such as the families of the factory workers, also gave them another unflattering nickname: "Penn sardines". This nickname translates into French as "tête de sardine", in reference to the heading of the fish that these women carry out daily. Used in the Douarnenez region since the 18th century, the term was later used to designate the distinctive headdress worn by these workers in the fishing ports of southern Finistère: a small white cap embroidered with ribbons, the shape and orientation of which resembled a small fish and its two tail fins.

This headdress is an exception in the sense that it is the only Breton headdress that is not attached to a specific area but is present in several territories: the Crozon peninsula, Pont-Croix and Cap Sizun, the Douarnenez area, the Bigouden area (for the ports of Sainte-Marine and Ile-Tudy) and the Giz fouen area (for the port of Concarneau). At the Loctudy cannery, the women went to the factory wearing the Bigouden headdress. However, most of them removed their headdress before entering the workshop. Their hair remained tied up in a bun by the " vouloutenn", This little black ribbon was used to hold the headdress on. The workers put on the headdress when they left the factory in the evening, once the work day was over.

A contemporary evolution of the perceptions of the profession

While living conditions at the seaside in the 19th century and until the middle of the 20th century were difficult and coastal populations lived in precarious conditions, the situation has changed significantly since the second half of the 20th century. During this period, the standard of living of fishermen improved significantly, as did that of fish cannery workers. Today, the perception of the cannery worker's job has improved significantly, both from the point of view of the employees and from outside the profession. The industry is now positively promoted, as shown by the gallery of testimonies from employees of the Compagnie bretonne in the modern premises of its production site in Penmarc'h.

Beyond these portraits, which show a sense of pride on the part of the employees of this cannery, it is the improvement in working conditions in French canneries that is important to highlight. While changes in national legislation to regulate working conditions have played an important role over the past 70 years, new factory managers have also played their part in this improvement. This is the case of Maria and Sten Furic, the two managers of the Compagnie Bretonne who, since taking over the family business, have changed their governance model in favour of a better integration of the employees and their needs[1].